Poe's Quarrel with Boston Writers

Beyond the Insults: What Boston Meant to Poe

In Hexameter sings serenely a Harvard Professor;

In Pentameter him damns censorious Poe.

Henry Wadsworth Longfellow,

Journal, February 24, 1847

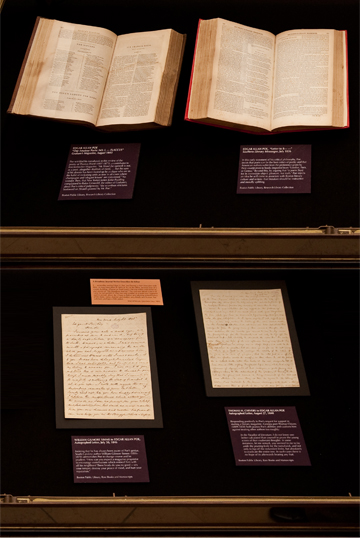

From the quiet of his study in Cambridge, Massachusetts, Henry Wadsworth Longfellow compared himself, calm and unthreatened, with "censorious Poe," a critic who "damned" other writers in his reviews. This view of Poe as excessively critical, even hostile, in his book reviewing, was widely shared from the beginning of his career to the end. There is no doubt that Poe earned his reputation as the "Tomahawk Man" one insulting review at a time. Over the course of his career, he argued, for example, that James Fenimore Cooper was "remarkably and especially inaccurate," Ralph Waldo Emerson a "mystic for mysticism's sake," and William Wordsworth a literary "pick-pocket." Indeed, Poe denounced Longfellow as a serial plagiarist and characterized the beloved professor-poet's Boston-based defenders as a group "of rogues and madmen."

Calling Bostonians in general and its writers in particular "Frogpondians," Poe brought both delight in literary combat and a distinct set of critical ideas to his career-long engagement with the city of his birth. But, when Poe railed against "Boston," what did "Boston" mean to him? Surely it wasn't the place his mournfully recalled mother Eliza had urged him "ever to love," nor the place where his first and last works were published. Nor was it the place to which he retreated after dropping out of the University of Virginia. Nor the place he was thinking of moving to only weeks before his unexpected death in Baltimore. No, the "Boston" Poe fought as a writer and critic was (at least in his own mind) a literary clique and a set of assumptions about what literature should be and do.

Beyond the insults, Poe's quarrel with Boston-area writers and editors had serious objectives. Among these were his desire to: help shape American literature; break what he saw as the grip of literary elites based primarily in New York and Boston; develop new ways of reaching a large but also diverse audience; and move poetry and fiction away from didacticism. That these objectives often focused on Boston is apparent across Poe's work, nowhere more so than in his 1845 essay on "Longfellow's Poems":

In no literary circle out of BOSTON–or, indeed, out of the small coterie of abolitionists, transcendentalists and fanatics in general, which is the Longfellow junto–have we heard a seriously dissenting voice on this point. It is universally, in private conversation–out of the knot of rogues and madmen aforesaid–admitted that the poetical claims of Mr. LONGFELLOW have been vastly overrated, and that the individual himself would be esteemed little without the accessories of wealth and position.