Poe's Quarrel with Boston Writers

OMG! Poe was right about Longfellow

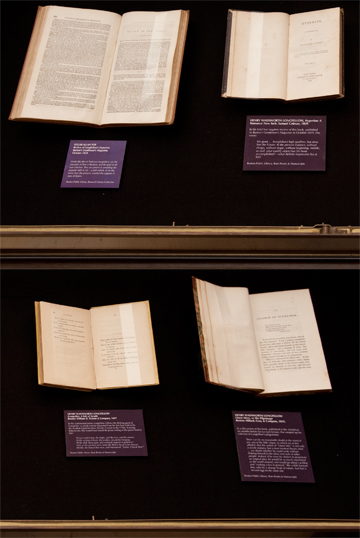

The Lyceum blow-up should be seen as the climax of a long conflict Poe waged against literary values he associated with Boston writers in general and Henry Wadsworth Longfellow in particular. From 1835 on, Poe kept his vulture eye on Longfellow's work. Mocking the "lofty thought and manner" of "Hyperion" in 1839, he noted that it lacked shape and design and would not be remembered. In a series of reviews starting in 1840, Poe charged Longfellow with plagiarism. The titles of his review essays–including "Tennyson vs Longfellow" (1840), "A Continuation of the Voluminous History of the Little Longfellow War" (1845), "More of the Voluminous History of the Little Longfellow War" (1845), and "Mr. Longfellow and Other Plagiarists" (1850)–suggest that the wealthy, celebrated Cambridge professor provided Poe with his most fiercely pursued target, a white whale for his inner Ahab. They also suggest that, unlike Ahab, Poe had a good deal of fun with this campaign.

In his review of Hyperion (1839), Poe placed Longfellow's rising fame in the long context of literary history. "We grant him high qualities, [Poe wrote] but deny him the Future." Looking back at both careers a decade later in his Fable for Critics (1848), James Russell Lowell came down emphatically on the side of his Boston friend, wryly calling out:

Who–but hey-day! What's this? Messieurs Mathews and Poe,

You mustn't fling mud-balls at Longfellow so,

Does it make a man worse that his character's such

As to make his friends love him (as you think) too much? ...

You may say that he's smooth and all that till you're hoarse

But remember that elegance also is force;

After polishing granite as much as you will,

The heart keeps its tough old persistency still;

Deduct all you can that still keeps you at bay,

Why, he'll live till men weary of Collins and Gray.

The intervening years have, obviously, not borne out Lowell's prediction. Like Lowell himself, Longfellow is rarely read today, even by school children, while Poe is an international literary and cultural superstar. But was Poe's take on Longfellow valid? Most of what Poe saw in Longfellow's poems–including their emphasis on moral preaching–contributed to the gradual shrinking of Longfellow's readership, his loss of the "future." But what about charge that Longfellow was not simply unoriginal and imitative but a literary thief, a plagiarist, indeed the "GREAT MOGUL of the Imitators"?

It's easy to assume that Longfellow–who chose not to enter the fray against Poe–was innocent and that Poe, always eager to call attention to himself by making a fuss, was not only vicious but wrong. Just look at the two of them:

In this corner, Henry Wadsworth Longfellow: the prosperous and much-loved poet and professor of modern languages at Harvard, living in the house on Brattle Street where George and Martha Washington had resided during the revolution.

And in this corner, Edgar A. Poe: the scruffy writer of periodical literature, the hoaxer and trickster determined to sacrifice "Truth" to "effect," the critic often criticized for being too rough, the Tomahawk Man!

And yet, for all this, looking back at what Poe called his "Little Longfellow War," here's what critics say:

Longfellow's works, published and unpublished, were pervaded by borrowings, sometimes explicit, more often unacknowledged, from other authors–so much so that on occasion it even seemed to him they hadn't been written by anyone in particular.

Christopher Irmscher, Longfellow Redux

Had Longfellow been candid, Poe's charge [that he stole from a specific Tennyson book] would appear today, as it must have appeared then, decidedly unfair; but Longfellow's [dishonest claim that he had not even seen the book prior to writing the poem Poe pointed to] ... in the circumstances tends to draw suspicion from the accuser to the accused.

Sidney P. Moss, Poe's Literary Battles: The Critic in the Context of His Literary Milieu