Poe's Quarrel with Boston Writers

Introduction

One of the best-kept secrets in Boston's literary history concerns the most influential writer ever born here: Edgar Allan Poe. And the secret is this: he was born here! Over the past 200 years, leading up to the bicentennial of Poe's birth on January 19, 2009, his connections to other East Coast cities–Richmond, Baltimore, Philadelphia, and New York–have been celebrated and memorialized. While each of these cities hosts a museum or historic house that commemorates Poe's standing as a local author, Boston has made itself conspicuous for its apparent determination to treat the master of mystery–America's first great critic and a foundational figure in the development of popular culture–like an undeserving orphan. This attitude is all the more fascinating because it can be traced back to the 1840s, involves a war of words as snarky as any from that time, and is based on a misunderstanding of the importance of Boston to Poe's development. It turns out that Poe the baby and Poe the writer and critic were born in the same place.

On October 16, 1845, at the height of his post-Raven fame, Poe was invited to read at the Boston Lyceum. Kept waiting for over two hours while the first lecturer went on and on, he read not a new poem, as requested, but the lengthy "Al Aaraff," written in his teens. Boston reviewers criticized Poe's tactlessness and noted that, though he was "raven-ous to be known," he had failed to entertain the rapidly shrinking audience. One editor in particular, Cornelia Wells Walter of the Evening Transcript, went after Poe with a vengeance, punning repeatedly on his name in a series of barbed attacks. In response, Poe assailed "Frogpondians" in general, implied that they were chronically asleep and insisted that he had been trying to hoax and insult them: to make "a fuss."

The response article Poe published in the Broadway Journal two weeks after the reading concludes with his most intemperate remarks on the city of his birth:

We like Boston [he wrote ironically]. We were born there–and perhaps it is just as well not to mention that we are heartily ashamed of the fact. The Bostonians are very well in their way. Their hotels are bad. Their pumpkin pies are delicious. Their poetry is not so good. Their Common is no common thing–and the duck-pond might answer–if its answer could be heard for the frogs. But with all these good qualities the Bostonians have no soul. ... The Bostonians are well-bred–as very dull persons very generally are.

While this story–rich in colorful banter–is animated by pique (wounded pride and hurt feelings), it also reveals a critical disagreement that marked one of the great turning points in American literature and culture. Indeed, the Lyceum blow-up should be seen as the climax of a long conflict Poe waged against literary, critical, and aesthetic values he associated with Boston. With the possible exception of Nathaniel Hawthorne, Poe thought that Boston reviewers praised local and regional authors far too much. Largely in opposition to what he saw as the preachy and moralistic work of New England writers determined to change the world one poem at a time, Poe developed the view that poetry and fiction should affect (rather than persuade) readers, not teach truths but provide pleasure.

Poe arrived at this position by writing stories and poems crafted to amuse, puzzle, and terrify readers and by rejecting the use of literature to advance particular causes or worldviews. In this way, he set himself free to invent or improve such popular genres as the detective story, science fiction, and the gothic tale of terror. Rejecting the "moral taint" of Longfellow's poems, the "excess of suggested meaning" of the Transcendentalists, and even Hawthorne's "monotonous" use of allegory, Poe became the writer celebrated everywhere for his ability to make readers laugh and tremble.

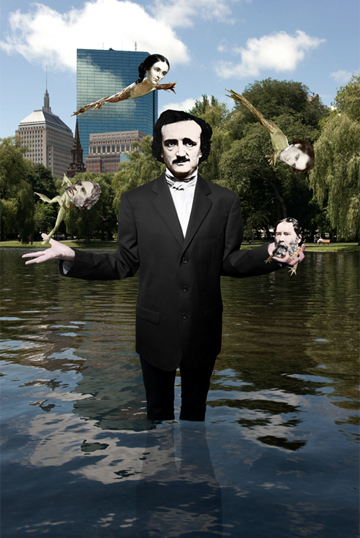

Despite the tragic outline of Poe's biography–his struggle with the early loss of his parents, his career-long and often desperate poverty, his troubled relation to alcohol–the writer and critic who wielded his tomahawk against the New England literary establishment clearly enjoyed sustaining his part of the argument. For this reason, we imagine him smiling while standing in the Frog Pond, juggling writers whose love of the didactic, he insisted, made them sound like croaking frogs!

Boston's long indifference to its connection to Poe extends back to the Lyceum lecture and its aftermath. But after 164 years it's time to see that the Poe-Boston conflict strengthened both sides of the argument: that American popular culture found its first great champion in Poe while New England writers charged into the 1850s determined to use literature to advance the truths and causes they held dear.

Mounted at the end of the Poe bicentennial year, The Raven in the Frog Pond uses materials from the Boston Public Library, the Susan Jaffe Tane collection, and elsewhere to tell the story of Poe's connection to the city of his birth. In its chronological recounting of Poe biography, the exhibit reviews the facts and presents information about Poe's time here. It engages urban legends that have grown up around the Poe-Boston story. It considers what Boston has done or failed to do to celebrate this native author. And it takes a close look at Poe's quarrel with Boston writers, focusing both on the clash of personalities and on arguments that influenced the development of American culture.