EDGAR ALLAN POE to JOHN PENDLETON KENNEDY

Autographed Letter, January 22, 1836

Boston Public Library, Rare Books and Manuscripts

EDGAR ALLAN POE to JOHN PENDLETON KENNEDY

Autographed Letter, January 22, 1836

Replica plate for ROBINSON CRUSOE by Daniel Defoe

19th century replica of a 1719 plate

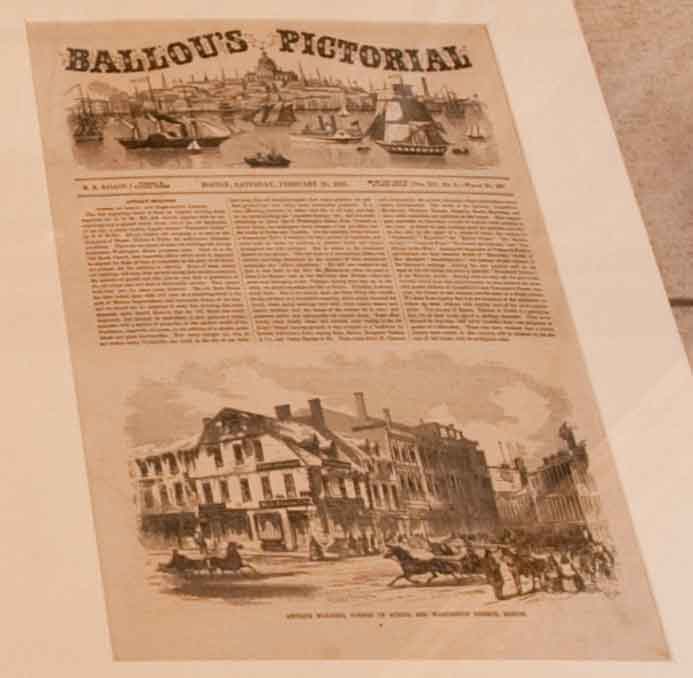

“THE OLD CORNER BOOK-STORE”

Boston Lithographic Society, 1904

HARPER BROTHERS to EDGAR ALLAN POE

Letter, June 1836

EDGAR ALLAN POE,

“X-ing a Paragrab,” in The Works of Edgar A. Poe, NY: J. S. Redfield, 1850,

vol. 4.

"Antique Building: Corner of School and Washington Street"

Ballou's Pictorial, February 21, 1857.

Poe, Boston, and the Publishing Industry

Boston-raised writer Nathaniel Parker Willis wrote in the 1830s that Boston had "denied me patronage, abused me, misrepresented me, refused me both character and genius." Willis eventually became the highest-paid magazine writer of his generation, though he did so in New York, not Boston. Boston-born writer Edgar Allan Poe struggled to find a city where he could be successful too. The publishing scene in Boston was still developing. At the time Poe published Tamerlane and Other Poems here in 1827, there were no major publishing houses in the city. Book printers in Boston were also retailers and, quite often, they were also the only retailer that sold the books they printed, severely limiting distribution. Those Boston-based printers who aimed for better distribution competed with Hartford, Connecticut as the publishing center in New England. The provincial nature of Boston publishing limited the distribution, success, and financial pay-off for Poe's first book. Still, throughout the antebellum period, American literature was growing, and publishing technology was developing too. As new printing machinery was emerging, however, other factors in the industry hampered the success of American writers, including Poe.

Type Setter (Date unknown)

During Poe's career and through the 19th century, printers relied on techniques that dated back to Gutenberg. In this long letterpress era, movable type was arranged by hand, bound tightly, inked and printed.